This FEELed Note is from Grace Henri who is a research affiliate leading project “Nostalgia Forecast”, which will investigate the complexity of eco-grief, and more specifically, how we mourn what we have not yet lost.

This summer, Kelowna burned before I even set foot here. About 7 days before my moving day. Every waking moment was consumed by checking the maps of a city I wasn’t familiar with. I watched as the fire crept closer to my landlord’s home, I struggled to understand how far away the flames could be seen. I wondered with dread how the air smelled, how the heat climbed. And despite this panic that desperately told my body “Stay!”, in late August, I left for Kelowna regardless. From the opposite coast, I boarded a flight filled to the brim with the “Nova Scotia wildfire crew”. Baffled as I sat next to a firefighter headed for the same destination as myself.

On my first day in Kelowna my landlord picked me up from the airport. We took the long way home, and she pointed out the evacuation line, showing me the parts of the mountain where the fire caused the most devastation. We drove through the lingering haze, under a sun that seemed wilted and hidden but threatening all the same. Upon arriving at my house, she helped me look around at the surrounding area. I felt shocked when she pointed out the charred tree line behind our house. Ensuring me, “you can still use the hiking trail, just turn around when you see black”.

It is in these moments that I feel floored by the question: how could life move on? Although it seems unthinkable, I remind myself: life doesn’t know what else to do. On one hand, I am amazed at our collective ability to adapt during the ongoing disaster of climate change. Amazed that we watch the land we know so dearly transform and change, and we carry on regardless. I am often baffled by our ability to cope, even in the times that feel the bleakest. At the same time, I worry that through this expectation for resilience we silence the pain that we simultaneously feel. I worry that resilience is resisting the urge to sit with our losses, to join together in despair, to slow ourselves to a halt. Is resilience, in part, a reaction to being told to carry on as normal despite the very abnormal changes our earth is sloping towards?

Much [AN1] of the literature surrounding climate change focuses on a social change dialogue. Frequently, ideas of hope and social action are used as an avenue to channel eco-anxiety into productivity and innovation. The focus on hope serves as a catalyst for conversation, protest, solutions; and yet, I fear our emotional state is often demoted as insignificant or unproductive.

In Generation Dread, Britt Wray frames social action as being possible only when emotions are honoured and given space to be wholly experienced (Wray, 2022). She outlines that first we must identify emotions as an appropriate and important response to our changing world, arguing that we are often expected to repress and deny ourselves of feelings; action is not enough, but rather, emotional processing and healing allows us to sustain and strengthen our place within an actively changing environment. The work of Rebecca Solnit acknowledges specifically that grief and hope can coexist, pointing to our ability to congregate around movements that demand social action despite being rooted in fear and sorrow (Solnit, 2016).

These perspectives highlight the importance of spaces dedicated to reflection, remembrance, and mourning what we’ve lost (and what is yet to come). Spaces that see action in the inaction and see collective mourning itself as transformative. As Solnit describes, “Purposefulness and connectedness bring joy even amid death, fear, chaos, loss.” (Solnit, 2010, pg. 3).

Environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht describes environmental grief as an “earth-related mental illness where people’s mental wellbeing… is threatened by the severing of ‘healthy’ links between themselves and their home” (p. 95). Environmental grief (or eco grief) encompasses the feelings associated with both current and anticipatory environmental changes. This is especially relevant within many Indigenous communities, where mourning the loss and change of land is not solely a contemporary experience, but one felt over centuries of colonization. In many communities, changes in land means a loss of certain cultural experiences and traditions, adding complexity to grief experiences. It is important to note that the effects of these changes will always be experiences the most dramatically by the marginalized, as the burden of climate change is heavily slanted towards Indigenous and racialized communities and those living in poverty.

The work of Ashlee Cunsolo describes grief as both individualizing and unifying (Cunsolo, 2012). Judith Butler describes mourning as transformative: “Perhaps mourning has to do with agreeing to undergo a transformation, the full result of which cannot be known in advanced.” (Butler, 2004, pg. 36). This rings especially true in our current climate of environmental change. Where our future is headed is uncertain and precarious. We have no choice but to mourn what we have already lost, and what we cannot predict – and most importantly, mourn this together.

When we think about the loss of a person, we have well understood culturally specific rituals of mourning. From funerals, to parades, to grief circles, we have demonstrated our understanding of what type of grief feels digestible to us. When we think of environmental grief, these same rituals have not been widely created. There is a lack of broadly constructed systems to evaluate our feelings around climate change, or to share the weight of these experiences (Cunsolo & Landman, 2017).

In a world often set on establishing individual responsibilities for the reversal of climate change, I argue that there is a benefit of grieving without the intention of resolution. Holding spaces for collective grieving is a radical resistance to the expectation of keeping environmental related grief suppressed, dismissed, and hidden from sight. Practices of mourning could both heal and mobilize towards change, through an understanding of mutual suffering and a shared vulnerability (Cunsolo & Landman, 2017).

In Panu Pihkala’s work on responding to environmental grief by naming emotions, she identifies the Finnish word Haikeus, one of many terms created in response to environmental change (Pihkala, 2020). The word is defined by Pihkala as the sadness associated with a changing environment, but a joyful gratefulness to the parts that remain intact. Western, colonial practices have silenced grief as a private, individualized endeavor. We are meant to grieve behind closed doors, separated from community, our own weight to carry. By normalizing hiding one’s grief, we begin to construct this process as shameful and burdensome (Cunsolo & Landman, 2017). This outlook denies the experience of grief as a helpful tool to carry us through painful transitions. Creating spaces for collective grief allows for us to process our emotions with solidarity, support, and gratitude.

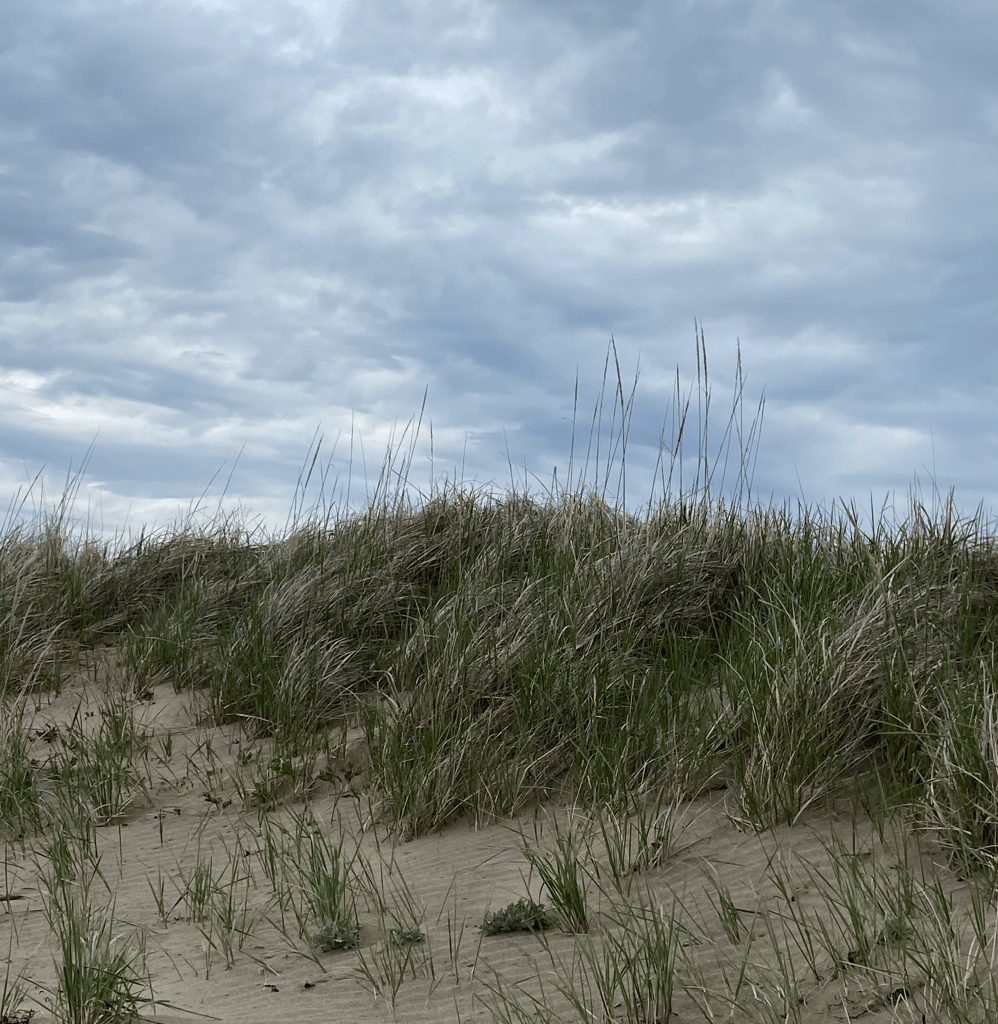

Early this October I woke up to frost on the ground. I walked to the bus stop near my house and saw snow dusted on the tips of the mountain. I was reminded of this summer when it felt like the heat would last forever. During this time, when I felt trapped in the fear of the unknown, I would often remind myself that the summer would fade, the fire would surrender, and in due time the snow would arrive. Like a light at the end of a tunnel, I assured myself, that if I could just hold my breath until then, I would be set at ease.

And I was correct, at long last the cold air had arrived. But that early morning, staring at the damp snow, feeling the cold air bite my neck, I realized that I felt no true relief. Through this realization I can acknowledge that we are living within a state of transition – one with no clear ending, no tidy resolution.

Our earth continues to change around us, the extent of which often feels quite unknown. In these moments I remind myself of what Solnit says, that grief and hope are not mutually exclusive (Solnit, 2016). Through these realizations I feel committed to the importance of creating community around environmental grief, feel compelled to reject the expectation of productivity by holding reflection and healing as an integral aspect of resilience. Furthermore, I can visualize the heartache and the joy we all feel within our environment as lovingly enveloped around one another.

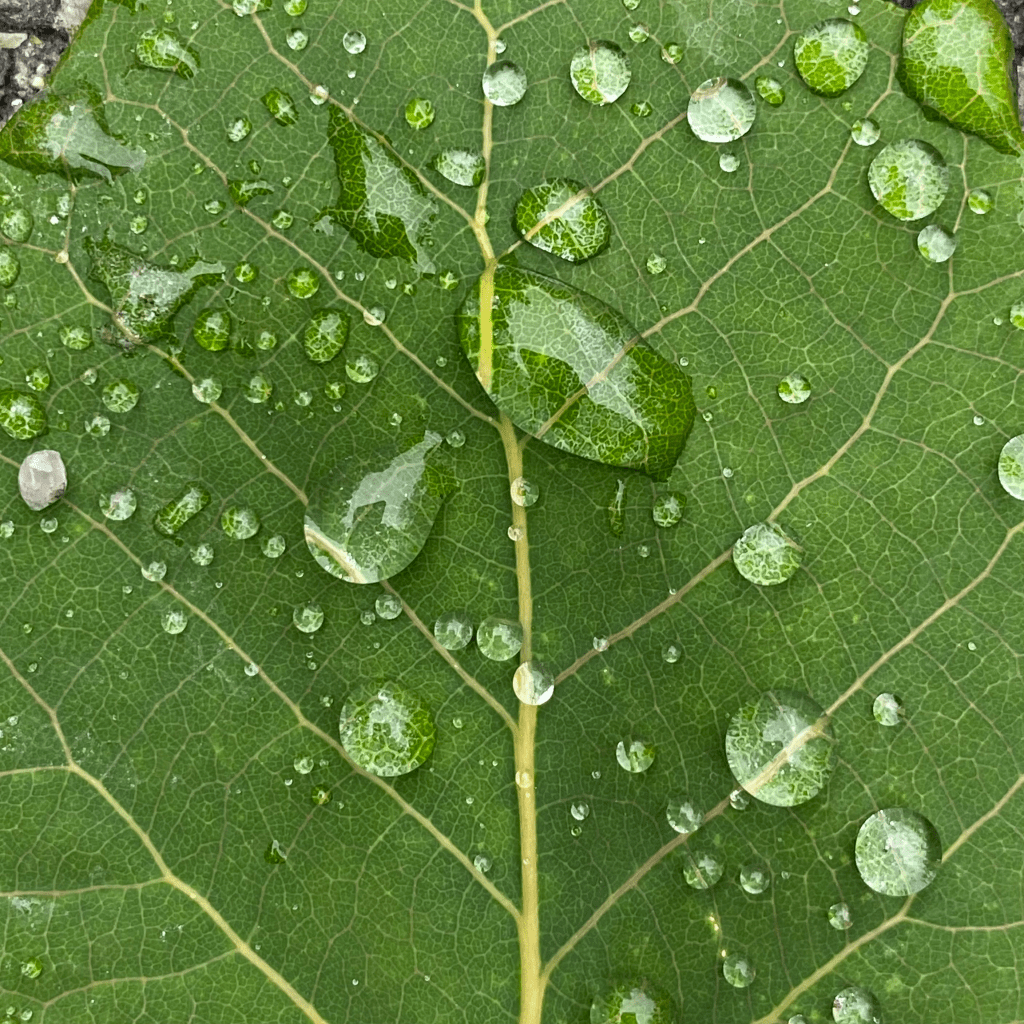

And so, I remain, far from the East coast, easing into my understanding of the changing landscape of BC. Despite this discomfort, when I think of my home in Nova Scotia, I feel a deep gratitude regardless of the distance. Grateful for the ocean tides that smooth the edges of old glass and leave them washed on shore to be found. Feel giddy when I think of my mother, crouched in the forest, catching frogs in her bare hands. Feel that sense of relief when hurricane season passes each year and the old oak in my front yard remains standing tall. Along with the grief, these are the things I want to share with others, listening too for the similarities we might find in each other.

I want to feel the symphony of emotions and experiences that bring tears to our eyes, that reject the urge for resolution, that stitch us closer together through the pain and the joy.

References

Albrecht, G., Connor, L., Higginbotham, N., Freeman, S., Kelly, B., Pollard, G., Sartore, G.M., Stain, H., & Tonna, A. (2007). Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australas. Psychiatry, 15, S95–S98.

Butler, J. (2004). Precarious life: The powers of mourning and justice. Verso.

Cunsolo, A. (2012). Climate change as the work of the mourning. Ethics & the Environment. 17(2).

Cunsolo, A., & Landman, K. (2017). Mourning nature: Hope at the heart of ecological loss and grief. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Panu, P. (2020). Climate grief: How we mourn a changing planet. BBC: Climate Emotions. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200402-climate-grief-mourning-loss-due-to-climate-change?utm_campaign=Ho

Solnit, R. (2010). A paradise built in hell: The extraordinary communities that arise in disaster. Penguin Books.

Solnit, R. (2016). Hope in the dark: Untold histories, wild possibilities. Haymarket Books.

Wray, B. (2022). Generation dread: Finding purpose in an age of climate crisis. Penguin Random House Canada.