A contribution from Daisy Pullman, FEELed Lab Associate Researcher for the ALT-2040 Project, which also includes researchers Natalie Forssman, Haida Gaede, Astrida Neimanis and past contributors Madi Donald and Emilie Ovenden. Read more here.

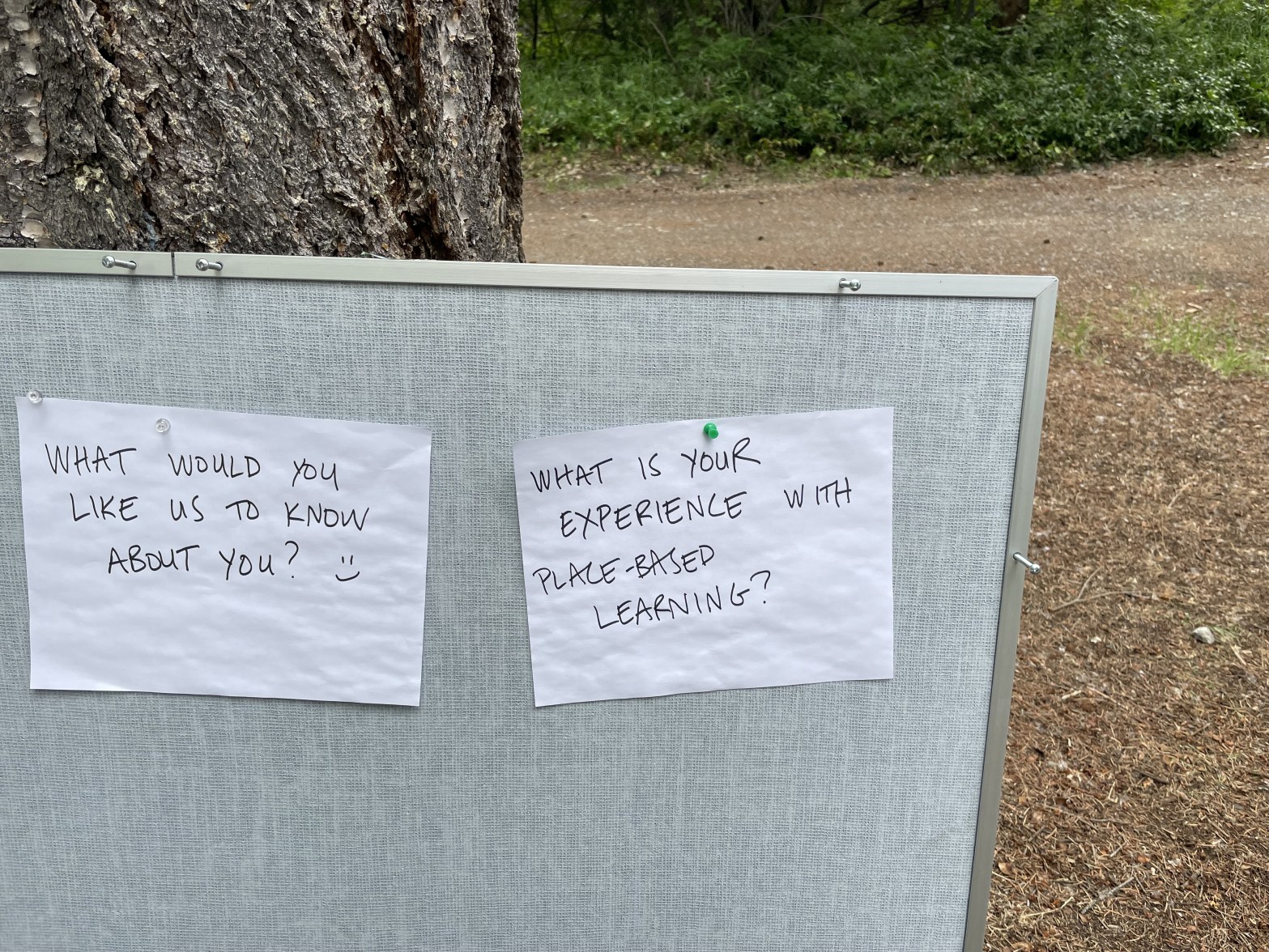

What does it look like to center inclusion in environmental education? How can place-based methods be made accessible to all? Over the last 8 months, I have been considering these questions as I work with FEELed lab colleagues to develop a course in place-based methods for UBC Okanagan students and community partners. A key dimension of this project from the start has been an emphasis on accessibility and inclusion. For us, this means offering opportunities for people of different cultural backgrounds, physical abilities, neurotypes, genders and sexualities, economic situations, and ages to meaningfully participate in place-based learning.

Environmental and place-based education has tended to assume a particular type of body; young, nondisabled, neurotypical, white, male, cis-gendered… ‘True’ nature, where place-based learning is supposed to occur, has been located as only out there, remote and rugged, difficult to access, and removed from obvious signs of human life. This definition of nature is inherently exclusionary considering the many affordances and privileges it requires to access (mobility, time, money, feeling safe in remote spaces, and so on). By reimagining the environments in which place-based learning can occur we open up the potential for truly inclusive learning. Why not a backyard? A classroom? A home? All are unique environments offering rich sensory experiences and opportunities for place-based learning. Moving beyond the artificial and exclusionary preconceptions of what constitutes a ‘true’ experience of place (typically a physical interaction with the ‘natural’ ‘out there’), we can begin to imagine an accessible and inclusive approach to environmental education and place-based learning.

Engaging with critical disability studies literature in the course of this project challenged many of my preconceived ideas of what accessibility and inclusion in education should look like. Rather than adapting as and when accommodation needs are disclosed by learners as tends to be the case, education needs to be designed with accessibility and inclusion considered and prioritized from day one. It cannot be an addendum or an afterthought, it must inform the entire pedagogical approach. Dominant ideas of what learning, and especially place-based learning, looks like, need to be disrupted and dismantled from the bottom up. In the brilliant article Cripping Environmental Education, which has greatly influenced my thinking on this subject, Jenne Schmidt writes:

Cripping environmental education is not merely about including students with disabilities into existing curriculum and pedagogical approaches, but rather calls upon all educators and scholars to disrupt the ways in which the philosophical foundations of the field rest upon compulsory able-bodied/sane assumptions.[1]

Critical perspectives like Schmidt’s will continue to shape the way I approach pedagogical design and teaching, and I am grateful to have been exposed to them in the process of working on this project. Accessibility and inclusion are far too often an afterthought in environmental and place-based education, and this project is one small step toward challenging this predominant approach.

[1] Schmidt, J. (2022). Cripping environmental education: Rethinking disability, nature, and interdependent futures. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 2. doi:10.1017/aee.2022.26