This FEELed Note is the first post from Tom Letcher-Nicholls, a PhD student in UBCO’s Interdisciplinary Graduate Studies program in Sustainability. His research focuses on the responsibilities, relations, and obligations of researchers on unceded territories

From the 19th-22nd of June, with the support of the FEELed Lab, I attended the 2024 biennial conference of the Association for Literature, Environment, and Culture in Canada (ALECC) with the theme of “Migrations”. The conference call asked us to think of migration in the most expansive sense: as shaped by specificities of place, history, and power; and as undertaken by humans and nonhumans alike.

The conference was held at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, which is situated on the shared traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishnaabe and Haudenosaunee peoples, part of the Dish with One Spoon Treaty between the Haudenosaunee and Anishnaabe peoples (Wilfrid Laurier University).

I was grateful to attend the conference with three other UBC Okanagan students: Emma Carey, who works on the FEELed Lab’s “Enhancing Access and Inclusion in Environmental Humanities Research Practice Project”; and MFA students Amy Wang and Roland Samuel.

During the conference, Ontario and surrounding areas experienced a “heat dome”, and while temperatures were around 30° degrees Celsius, the weather reports said it felt around 40° due to the humidity. I felt acutely aware of the experience of “weathering” (described so powerfully by Neela Rader in their FEELed Note: https://thefeeledlab.ca/2024/04/14/dear-mill-creek-sorry-for-everything-p-s-i-love-you/).

The boundaries between my body and the enveloping humidity felt blurred, and it felt like an affirmation that we are ourselves bodies of water in a watery, heating world.

The opening sessions of the conference touched on migration, movement, access and power in powerful and wrenching ways. A particular highlight was Jordan B. Kinder’s opening address, which took the form of an extended land acknowledgement.

Jordan asked us to consider our travel to the conference – where we came from, how we got there, and the things that enabled and troubled our travel.

My thoughts went to the Syilx (Okanagan) People on whose territories I now live, work and play; and to the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people of the Kulin Nation of south eastern Australia, where I was born and grew up.

Amy and Roland were on the same panel, which for me was one of the most moving of the conference. Amy read and discussed their poetry while Roland’s talk focused on one of his sculptural works which was displayed at UBCO’s art gallery. Their talks touched on migration, place, memory, and family, and it was a privilege to be there.

Emma led a speed zine workshop. We started with questions and prompts about our journeys to the conference. This discussion led us to creating collaborative zines that all touched on access and inclusion in multiple, generous, and generative ways.

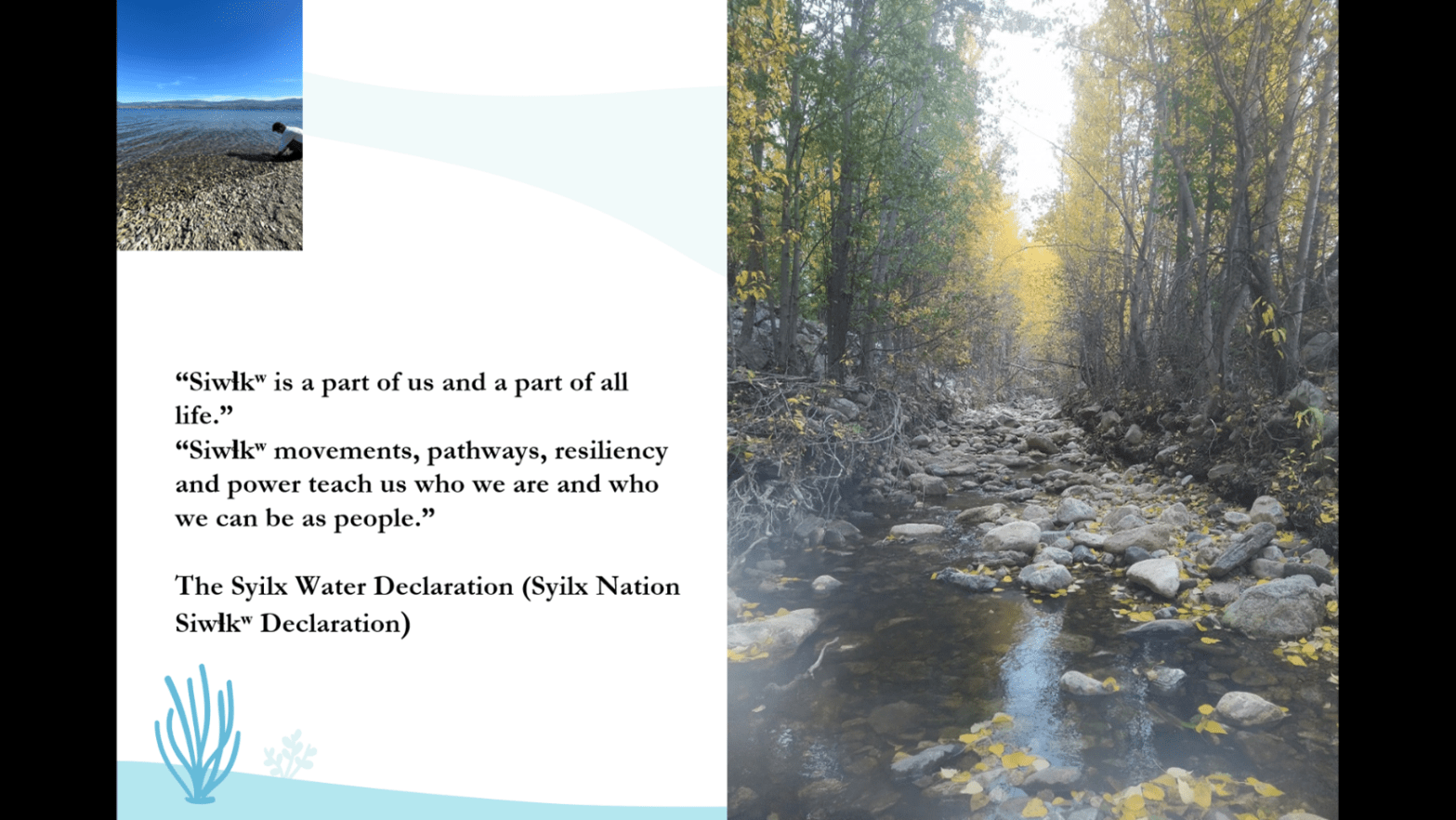

My paper, “Migration, Research Mobility, and Place: Learning from Water in the Contemporary Academy”, explored how water, as a migratory but also situated substance, might help us imagine ways of decolonising teaching and research in the field of literary studies.

My hope was to reflect on our own positions as researchers in the academy – our obligations and responsibilities, and the ways that we can shape our teaching and research (especially in literary studies) with intention, care and responsibility.

I began by discussing how my chosen movement/migration to Canada, with its very different climate to Australia, has made me more attuned to the seasons. I described how in Kelowna the start of spring is heralded by the appearance of small yellow flowers known in Nsyilxcen as smúkʷaʔxn and in English as the “Arrow-leaved Balsamroot/Spring Sunflower”.

According to the “Plant Guide” from the na’ʔk’ʷulamən garden at Okanagan College, for Interior First Nations people, this flower was an important source of food, medicine, and technology. But the Plant Guide says something else about the smúkʷaʔxn (9):

An interesting note about this plant is its role in preparing young Syilx boys to walk silently and softly across the forest floor when wearing moccasins. The boys wrapped their feet in balsamroot leaves and challenged themselves to walk as far as possible without tearing the leaves.

In “From Classroom to River’s Edge: Tending to Reciprocal Duties Beyond the Academy”, Todd describes “[t]he river—sipiy—that runs through Edmonton [as] a methodological and philosophical teacher in my work” (92).

For my part, I think of the smúkʷaʔxn as itself a body of water like the sipiy, and as a “methodological and philosophical teacher.” Learning from the flower, I wonder if I will be able to tread lightly, with intention and care, in this new place.

My talk turned to texts as “methodological and philosophical teachers”. In Small Bodies of Water (2019), a piece of creative non-fiction nature writing, writer Nina Mingya Powles quotes Aotearoa writer K. Emma Ng, who asks: “How can we belong here, become ‘from here’, without re-enacting the violence that is historically embedded in the gesture of trying to belong” (246-247).

Powles, who is also from Aotearoa but of mixed white and Malaysian Chinese identity, suggests that “it begins with understanding what it means to put down roots on stolen land, and doing so with intention, with care and respect. It means collective responsibility, and working towards a better world for Indigenous and displaced people” (247).

I closed by suggesting that water might help us attune ourselves to these teachers. In Wild Blue Media, Melody Jue argues that most models of literary theory operate from and assume “a terrestrially inflected model in which a human interpreter remains on the ‘surface’ of a text and chooses to either look at the surface or peer into its depths” (56).

Jue suggests, however, that “Oceanic conditions of observation” and immersion help us reconsider “the binary of surface/depth” and so “by thinking through the ocean, we can begin to develop a sense of milieu-specific environments of critical practice that differently implicate the human observer and their normative orientations” (57).

If we are bodies of water, we are also largely land creatures and our research practices are forms of “situated knowledges” (Haraway, 581). But what would it mean to submerge our research practices and disciplines, as Jue suggests?

Doing so, I think, might just help us think about migration and belonging, as Powles says, with intention, care, respect and responsibility (Powles, 247).

Work Cited:

Haraway, Donna J. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective”. Feminist Studies. Vol. 14, No. 3 (1988). 575-599. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Jue, Melody. “Introduction: Thinking Through Seawater”. Wild Blue Media. Durham: Dke University Press, 2020.

Okanagan Nation Alliance. Syilx Water Declaration. July 31, 2014. ONA AGA Spaxomin, British Columbia. https://www.syilx.org/about-us/syilx-nation/water-declaration/

“Plant Guide”. Okanagan College. na’ʔk’ʷulamən garden. Available here: https://www.okanagan.bc.ca/story/nakwulamn-garden

Wong, Rita, and Cindy Mochizuki. Perpetual. Nightwood Editions, Gibsons, BC, 2015. Wilfrid Laurier University. “Land Acknowledgement”. https://www.wlu.ca/about/campuses-and-locations/assets/resources/land-acknowledgement.html