This blog was written by the FEELed Lab core-member and Place-Based Pedagogies Project Research Assistant Manuela Rosso-Brugnach (PhD Candidate at UBCO) under supervision of Dr. Natalie Forssman and Dr. Astrida Neimanis.

As I reflect on our session with the wonderful Dr. Lindsay Kelley, as part of the FEELed Lab Place-Based Pedagogies Project, during her facilitation on how food practices can serve as mediums for artistic expression, scientific inquiry, and polyvalent-living the world, I reflect on the words, the thoughts, the senses circling the space as the guests share their views on food, taste, recipes, composting and the entangled growth of a pumpkin plant vine that secures its neighboring growth upright in Erin’s garden (Research Affiliate of the FEELed Lab).

As we taste a diversity of fermented goods, locally grown red and white cabbage cuttings seeped into vinegar, sourdough bread baked with transoceanic bio infused bacteria from across the multifarious puddle we call sea, rhubarb jams and blue cheeses, spanning a lively body of traditions, plant species and bacteria, the impartiality of taste propelling the air in the room — neither flattering nor sparing us while experiencing their sensorial worlds. The way they cling onto our mouths, uncompunctious, toting and recomposing the histories of their making in every bite. The sour bitterness of burnt bread, the resinous tang of tar, the acrid smoke of charred wood reaching us, spontaneous in holding, with stories far older than our tongues.

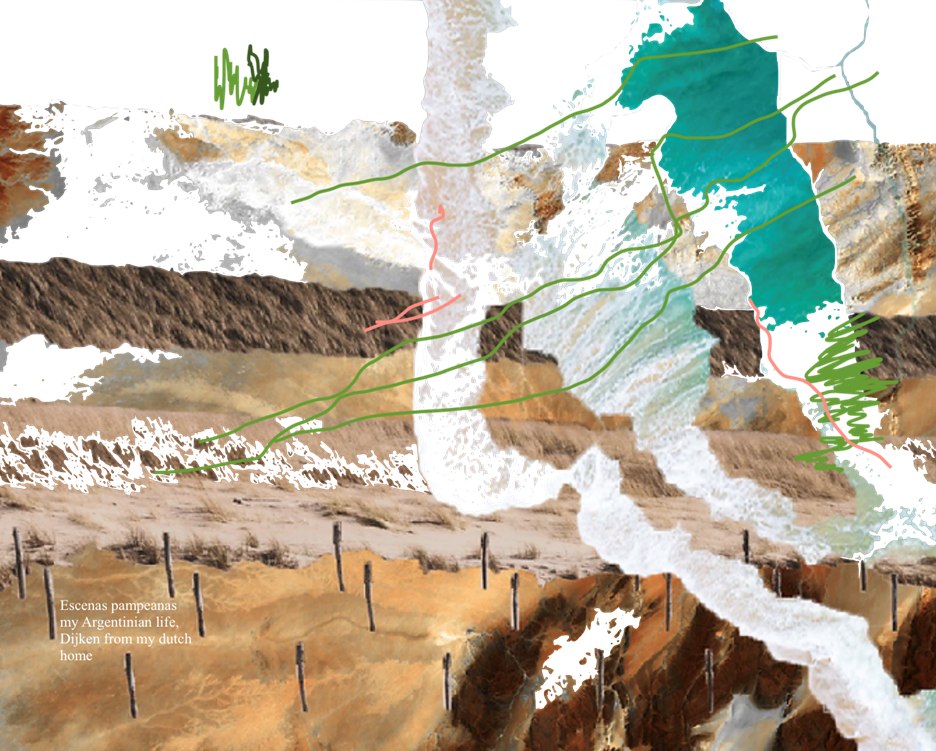

The excitement of sharing flavours, stories, sensations, meeting us where we are, drawing on the tongue-languages we carry, the cultures of our parents and elders, the sensations we remember, perhaps even those we have not yet remembered to forget, the potential delicacies we carry in our pockets as we start the day, and the sites and ecologies we travel to come around the table and meet. To taste a place is to metabolize its biodiversity, to translate its flavors into something fleshly yet unspeakable during the encounter, sedimenting itself onto us as we chew. As I felt the burnt landscapes of tar liquorice, I thought of the places I’ve lived, where I learned to taste and word the world anew:

In Spanish, “El hambre agudiza el ingenio.” could be translated to “Hunger sharpens ingenuity”. The flavors of Argentina mirror this resourcefulness: the bittersweetness of dulce de leche, the earthy depth of mate made by my mother in a hurry while we tell each other stories about the day to come, the sharpness of a ripe lime from the garden to add to our dinner that day. During one of my trips to the dense subtropical forests of Misiones, I remember walking along the edge of the Iguazú River, the air alive with the scent of wet stone and iron-rich clay. I didn’t know it then, but this was the language of sediment, of erosion, of rivers carving their stories into my stone of a home.

In German, “der Geschmack bleibt neutral, aber die Erinnerung füllt die Lücken”, meaning “Taste remains neutral, but memory fills the gaps”. Germany’s culinary traditions—dark rye bread, smoked sausages, Sauerkraut—my grandmother Lori carefully placing them on the table as we sit around a candlelit auburn surface pondering as Alwin tells us stories about the dancing neighborhood birds for Abendbrot. I remember walking around the house, the air was cool and damp, and the scent of pine resin was sharp, almost medicinal. I paused at the edge of a clearing where an ancient oak had been struck by lightning. The taste of the air around that oak was metallic and slightly sweet, like the memory of rain meeting embers of sunlight.

In Dutch, “Smaak is een brug tussen zintuigen en verhalen”, translates to “Taste is a bridge between the senses and stories”. The bittersweetness of drop (licorice) or the creaminess of hagelslag (chocolate sprinkles) as my dear friend Lauren cascades amidst a tumbling pile of dirty dishes while we exuberantly perform our reactions to the day in a frenzy. Friendship in the city despite a series of failures laying our mouths to rest into sugar-covered neatly stacked bread.

And in Ireland, “Is maith an t-anlann an t-ocras.”, translates to “Hunger is the best sauce”. The damp air heavy with rain, I felt the taste of belonging tied to the metallic tang of the Atlantic, where salt clung to my lips as I hungrily looked towards my partner observing the vast, darkened ocean waves ahead. A rugged landscape carried by the wind sweeter than anything. I lived in a small village where the dark water met the land with a kind of relentless and tranquil synchronicity. The mornings began with mist rolling off the cliffs, softening the edges of the fields, memories of the sting of the wind on my cheeks and the tang of the sea on my tongue, for me: This is what it meant to live at the edge of something awaiting.

Kelowna holding my hand as I began my trip into this world, listening as I sit in the land awaiting new tastes.

Translingual Poem: Lengua de Cenizas / Tongue of Ash / Zunge der Asche

En el sabor del río and the taste of the river, Im Geschmack des Flusses, el aire salado del océano, the salty air of the ocean found in der salzigen Luft des Ozeans,

la resina de los árboles quemados amidst the resin of burnt trees circling der Harznote verbrannter Bäume,

sentí voces que no tenían palabras. Voices without words, und fühlte ich leise Stimmen der

Tierra mojada, tasting wet earth, der Geschmack der nassen Erde,

las raíces rotas por tormentas, of roots broken by storms, nach Wurzeln die von Stürmen abgebrochen wurden, a cicatrices en la lengua and stains on the tongue, Nasse Narben auf der Zunge angränzend aufgefangen, No me necesitas mirar me decían.

Living Resonant Archives

Taste lingers, lively, carrying stories of place, culture, and acquired home-resounding tastes and sounds. The bitterness of burnt bread, the resinous tang of tar, or the complexity of fermented foods speaks not only of their making but of the landscapes, traditions, and ecologies they emerge from and life with. Acquired tastes—those we learn to venture with— building bridges between memory and presence, between the density of the familiar and the gleaning almost no-longer unfamiliar. Dr. Lindsay Kelley’s facilitation on fermentation invited us to reconsider taste as a form of translation and transformation. The fermented goods we shared, not just flavors but entanglements of microbes, species, and a telling of multiple and unendingly vivid stories. Kelley highlighted how fermentation mirrors the processes of adaptation, growth, and collaboration that shape our undulating relationships with the world.

To acquire a taste is to metabolize more than flavor—it is to witness and carry the sensorial histories of a place, to let its biodiversity sediment itself within us. As we tasted, the languages of land and memory intertwined, reminding us that taste is a practice of attunement, a digestive, felt way to inhabit and translate the multiplicities of place, ecology, and being in making. Kelley’s work for me reframed this act, showing how the sensory world offers a medium for connection, inquiry, and the delicate stitching together of histories shared and onward looking.

Thank you for all the contributors and participants of the session, to Lindsay, Astrida and Natalie who greatly contributed to this work.