This blog post was written by FEELed Lab visiting artist/scholar Liz Toohey-Wiese, who is exploring the complicated topic of wildfires and their connections to tourism, economy, grief, and renewal…

On Sunday, February 2nd, I drove from Vancouver to Vernon, where I am staying at the Caetani Center as an artist-in-residence and joining the FEELed Lab as a visiting artist and scholar. It was the first snowy day of the winter in the Lower Mainland, so I opted for the lower-elevation route to Vernon via Kamloops, to try to avoid the worst of the driving conditions. This stretch of Highway 97 holds significance for me—I installed a billboard here for six months in 2020, and since then, I have used this highway to access fishing spots, to go scouting for morels in the wake of the White Rock Lake fire, and to go swimming in Monte Lake on the hottest days of summer.

My drive was uneventful until I reached this stretch. Suddenly, I was in total white-out conditions, unable to make out the edges of the road. I was shaking as I drove. I was listening to a playlist of Hank Williams’ gospel songs. To distract myself, I nervously sang along to “I Saw the Light”, the irony not lost on me as I squinted into oncoming cars’ headlights.

At one point, the line of cars ahead of me slowed drastically, hazard lights flashing. As we snaked along in the dark, I noted something. As my experience of driving on interior BC highways is often one of agitation, fear, and animosity (ie. cursing semi-trucks passing me on the Coquihalla, cars overtaking mine at the last minute on high and narrow mountain passes, watching in horror as someone does 130 km/h+ in snowy conditions on the Connector, etc.), I was surprised in this moment that my feeling was that of mutual caretaking and camaraderie with the other cars. In that moment, I felt supported. I felt led by people who (hopefully) had more experience than me driving in these winter conditions on this road, our flashing lights beacons to each other that said: “Here, follow me”.

I arrived at my friend’s house for dinner around 8 pm and brought a bottle of recently purchased mezcal inside with me. We toasted to my safe arrival, and my hazing into the Okanagan winter. I felt capable and strong.

A few days later, in much better weather, I drove to Woodhaven to lead my workshop at the FEELed Lab. As participants gathered, we pulled our chairs closer, cozying into the kitchen. I shared what’s been on my mind lately as an artist, educator, and someone deeply invested in the collective survival of the planet: How do we see clearly what is happening, acknowledge it honestly, and still do the work needed to care for the places we love?

I’ve been thinking about despair as a natural reaction to our current reality. Grief for the world we love is not only understandable, but necessary. We will be better activists if we learn how to tend to our own emotional needs, to take care of ourselves by learning ways of letting these strong emotions come up, and pass through us.

A few years ago, I experimented with making paint from wildfire ash, hoping to use it in workshops for those grappling with ecological grief. It mirrored the broader question: How do we face what’s happening, and use it to create a future we want to see? When wildfires first entered my paintings in 2018, they lingered at the edges of the landscapes I was painting. Within a year, they were front and center. My art practice has become a way to look more and more directly at the climate crisis.

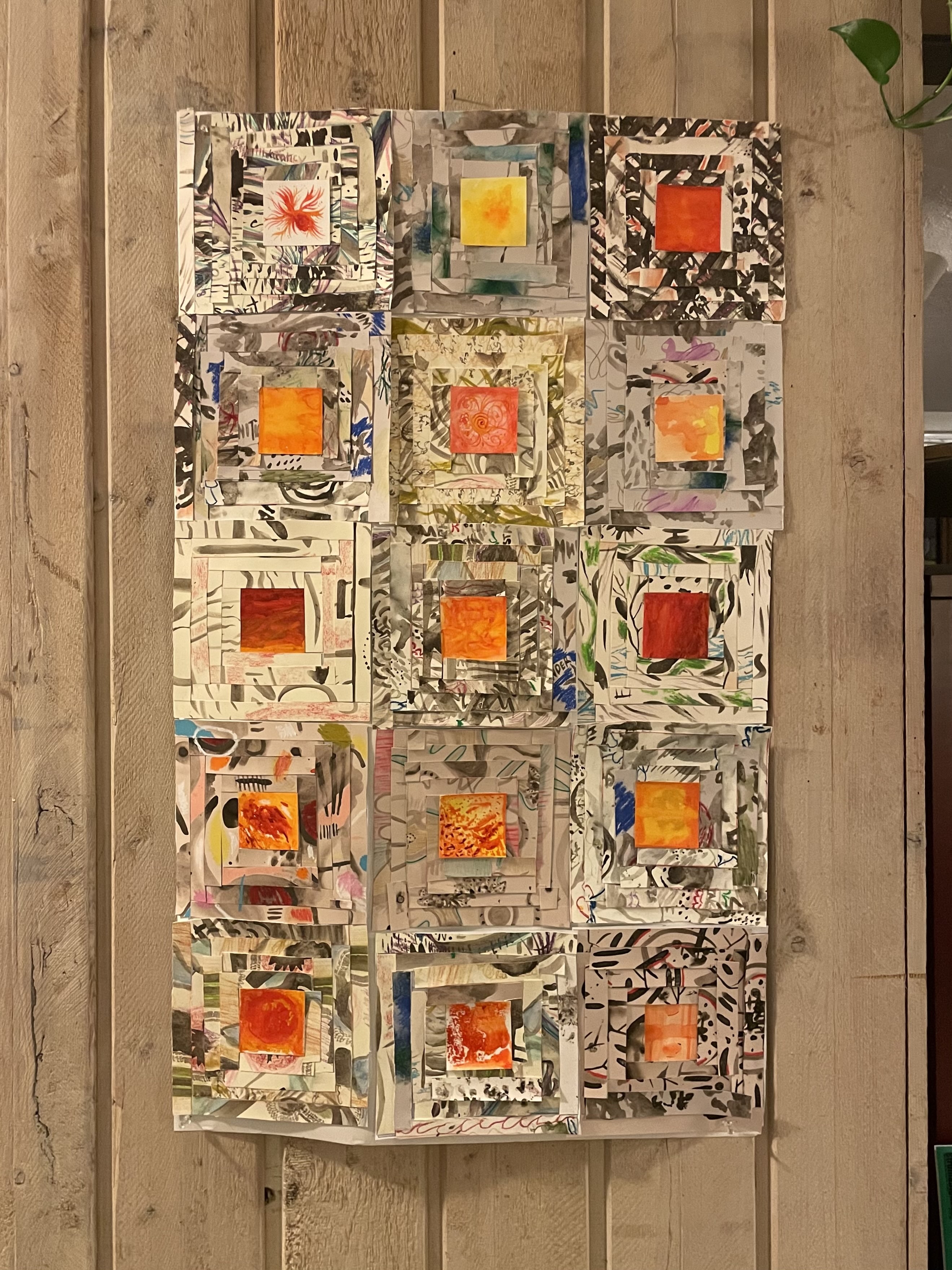

In the workshop, I invited participants to engage with materials, visualize their emotions about climate change, and introduce color into their compositions as we reflected on the strength of community support on working through these feelings together. We cut up and collaged our paintings, transforming them into paper quilt squares. We followed the traditional “Log Cabin” pattern, where a red square center represents the hearth of a home. We talked about the symbolism of interlocking rectangles in the quilt pattern—how they visually echo community support.

As each participant added their square to the collective quilt, our satisfaction grew in the act of making something beautiful together.

When I teach classes or workshops about ecological grief, I sometimes leave wondering, “Was that too much?” But each year, that self-doubt quiets. Each year, I become more convinced of the importance of grief work. Each year, I feel more certain that it’s okay to talk about suffering. The first book I read on ecological grief was Dahr Jamail’s The End of Ice. I saw him speak at SFU in 2019, then brought his book with me on a trip to visit my brother, a climate scientist, in Germany. Sitting in a café in Kiel, I read the conclusion of the book and felt tears well up. It was a relief to have someone give me permission to feel overwhelmed, confused, and powerless—watching beloved landscapes burn, experiencing summers thick with wildfire smoke, witnessing familiar cedar trees slowly dying from repeated summer droughts in the region I grew up in. Jamail was the first one who introduced me to the idea that grief is not only natural, but generative.

He quotes storyteller Stephen Jenkinson:

“Grief requires us to know the time we’re in. The great enemy of grief is hope. Hope is the four-letter word for people who are unwilling to know things for what they are. Our time requires us to be hope-free. To burn through the false choice of being hopeful and hopeless. They are two sides of the same con job. Grief is required to proceed.”

I’ve been trying to articulate this idea to friends who are struggling with the weight of doing good work in a world that often moves in the wrong direction. Policy reversals, setbacks, the feeling of losing ground—it’s exhausting. I’ve found myself saying: “Even if things don’t work out the way we want, what better way to spend our time?” For some, that time spent means attending blockades or protests. For others, it’s making art, writing, reading, thinking. I haven’t always been eloquent in expressing this, but then I found Václav Havel’s words:

“Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something is worth doing no matter how it turns out.”

Like the cars guiding me on my winter drive, I look to wisdom traditions that teach us grief is okay. “Here, follow me” requires trust in another’s guidance. I am happy to be led—and to lead others into the dark places within themselves, proving that from those spaces, there is still something beautiful to create, together.