This FEELed Note was written by Clara Kleininger-Wanik. You can watch Clara’s multispecies documentary, Thirsty, here!

The first thing I found in the studio at the FEELed Lab, in the middle of Woodhaven Park, where I was to stay for five weeks: a diary, logging 11 years of humans who have stayed in this room. On the first page, there is a list of birds someone spotted in the park, all names I did not know. Slowly, a multispecies history unfolds: in October, someone took out the spiders on the day they moved in (later I learned that the spiders come inside in October, to prepare for winter). Just the month before we arrived, there were critters, and someone else preferred to move out (later, I found out who the critters were).

I was fascinated by these intimate traces of encounters. I was here to collect some of my own: what I could gather, with my camera and sound recorder, about life in the park and why it was suffering. I was continuing an exercise I had started as part of my PhD fieldwork (in anthropology and film), on the Pacific coast of Mexico. I had spent all of last year in a waterworld and done a lot of thinking on what filming a waterworld means: Immersion? Deep blue? Changing colours throughout the day?

In Woodhaven, I wondered: how can I film a lack? A slow drying out? Parched land, still trees, only at night their large dropping branches can be heard. This I learned: the cottonwoods of the park are riparian trees, though adapted to live with a measure of drought. When they dry out, they cut off their limbs, starting from the top. If you live in or near the park, you can hear the branches crashing at night. Only those who share a common life with the park are able to observe how it is changing in the smallest of details.

These are some of the thoughts and building blocks which came to gather to make Thirsty, the short film that grew out of my encounter with Woodhaven Park:

It is through our bodies that we share the world with other living beings.

Through our bodies, also, we can communicate with them. Astrida’s (Neimanis 2017) work guided me here: her reflections about what water as a substance makes happen in our bodies – when drinking a glass of water for instance – made me think about the physical effects of its lack. As we experience the world through our bodies and never without them, I started there: what does thirst feel like?

“Thick tongue and itchy throat…. yeah, it’s quite uncomfortable” (Thirsty, 0:20) “It’s that aching in your being for moisture. Everything tightens up and everything shrinks up.” (0:30)

Filming involved accompanying participants on long walks through the park in the hot Kelowna summer. At the end of each walk, I asked them to describe being thirsty. Listening, one can almost feel the thirst oneself – a kind of bodily resonance. And if we can imagine human thirst, perhaps we can extend this sensitivity to other, more-than-human bodies as well. In the film, seeing the drying out, broken, and cut trunks of cedars and cottonwoods while hearing about thirst suggests empathy beyond the human: what might these other bodies be feeling?

Meeting others

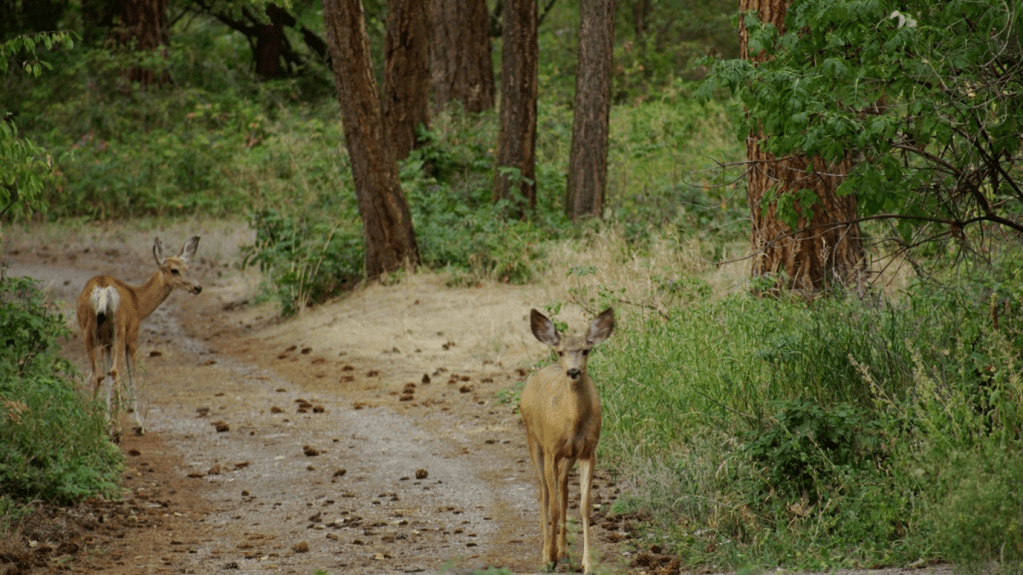

The park was a new environment for me, all plants foreign. To learn it, I was content to pay attention to the small, practicing the arts of noticing Anna Tsing (2015) proposes. I learned some rookie skills of tracking, bought a trail camera. But most of all, I spent time quietly, waiting and listening, ready for getting to know each other. By daily repetition, I learned the rhythms of the mother deer and her two fawns and the great horned owl who hunted just at dusk. But I also had to consider how the other living beings of the park see me, recognising that “seeing, representing and perhaps knowing, even thinking, are not exclusively human affairs” (Kohn 2013,1). To draw attention to this, the film has a scene showing the cautious exchange of gazes between the mother deer and me.

Humans on the land: feel, smell, see the drought

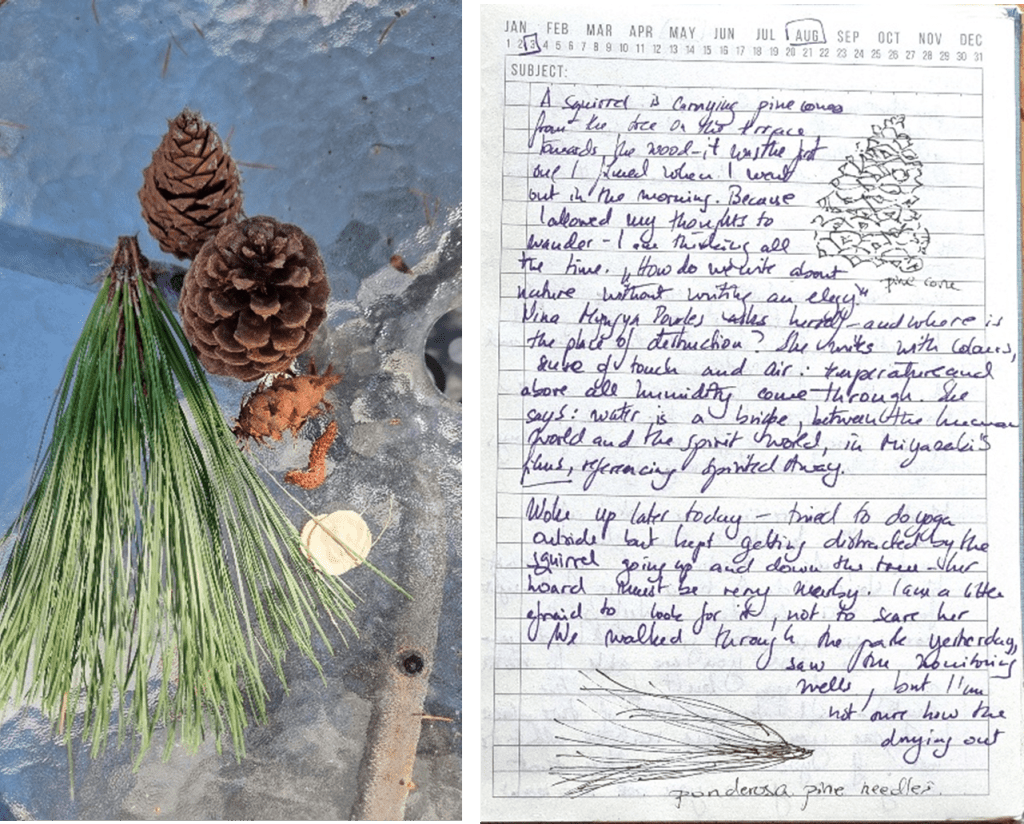

It is the heart of the film that it could draw on the love its human neighbours feel for Woodhaven (https://www.friendsofwoodhaven.ca/). Thanks to long, careful observation, they notice changes in the park with all their senses: in temperature – it is not as fresh as it used to be in the cedar grove, smell – it does not smell like skunk cabbage (a pungent musky smelling wet-land plant) anymore, and the ponderosa pines’ vanilla scent seems stronger when they are heat stressed. Woodhaven’s neighbours keep an imaginary and actual archive of what the park used to be like, and our conversations circled back to place attachment: how the park is made through relationships to others – the human friends who no longer are here and the other animals, who offered brief encounters or co-living.

A guiding thread in my work has been learning how Indigenous knowledge can open new ways of understanding connection to land and its more-than-human inhabitants. Water is central to Syilx ontology, as can for instance be seen in the Water Declaration (https://syilx.org/about-us/syilx-nation/water-declaration/). Briefly joining a Nsyilxcn course and a workshop on the web of life at the Sncewips Museum (https://www.sncewips.com/), as well as the wonderful knowledge of Coralee Miller, helped situate Woodhaven’s struggle within the ongoing effects of settler colonialism and the transformation of the unceded Syilx land under colonial draining, agriculture and urban development, as well as consider how the vision of land back might extend care and restoration to the entire multispecies community.

Credit: Clara Kleininger-Wanik

Afterword

Through our bodies and senses, we can feel the park’s slow but pervasive drying, which affects all. Bound into the urban fabric and the shadows of colonialism and capital (the park had been parcelled up in plots before being saved from the fate of the surrounding areas by virtue of its remaining wetland properties), the creek that feeds the park has been turned into a water licence, a tap turned on and off to keep the homeowners unconcerned while everything is drying out. Nevertheless, the film does not end on a dispirited note but reflects the willingness to fight that its human neighbours, including the fabulous FEELed labers who made me feel at home, have expressed. Long after we returned to Europe, I received a message that brought me joy. Sue, who now lives in what used to be our rooms in Woodhaven, had an awe-inspiring encounter. She thought about sharing it with me, and so, I still feel a part of the Woodhaven ecosystem, now imagining what autumn must look, smell and feel like in the park.

Credit: Susan Reid

References

Kohn, E. (2013) How forests think : toward an anthropology beyond the human. 1st ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Neimanis, A. (2017) Bodies of water posthuman feminist phenomenology. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Tsing, A.L. (2015) The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. 1st edn. Princeton: Princeton University Press.